Post originaly done on Codavel’s blog

HTTP is the current de facto network protocol that supports most of the Internet. Whether we are watching a YouTube video, checking a friend’s Instagram or buying that plane ticket to a conference on the other side of the world, HTTP is the protocol used by our web browsers or mobile devices to communicate with web services.

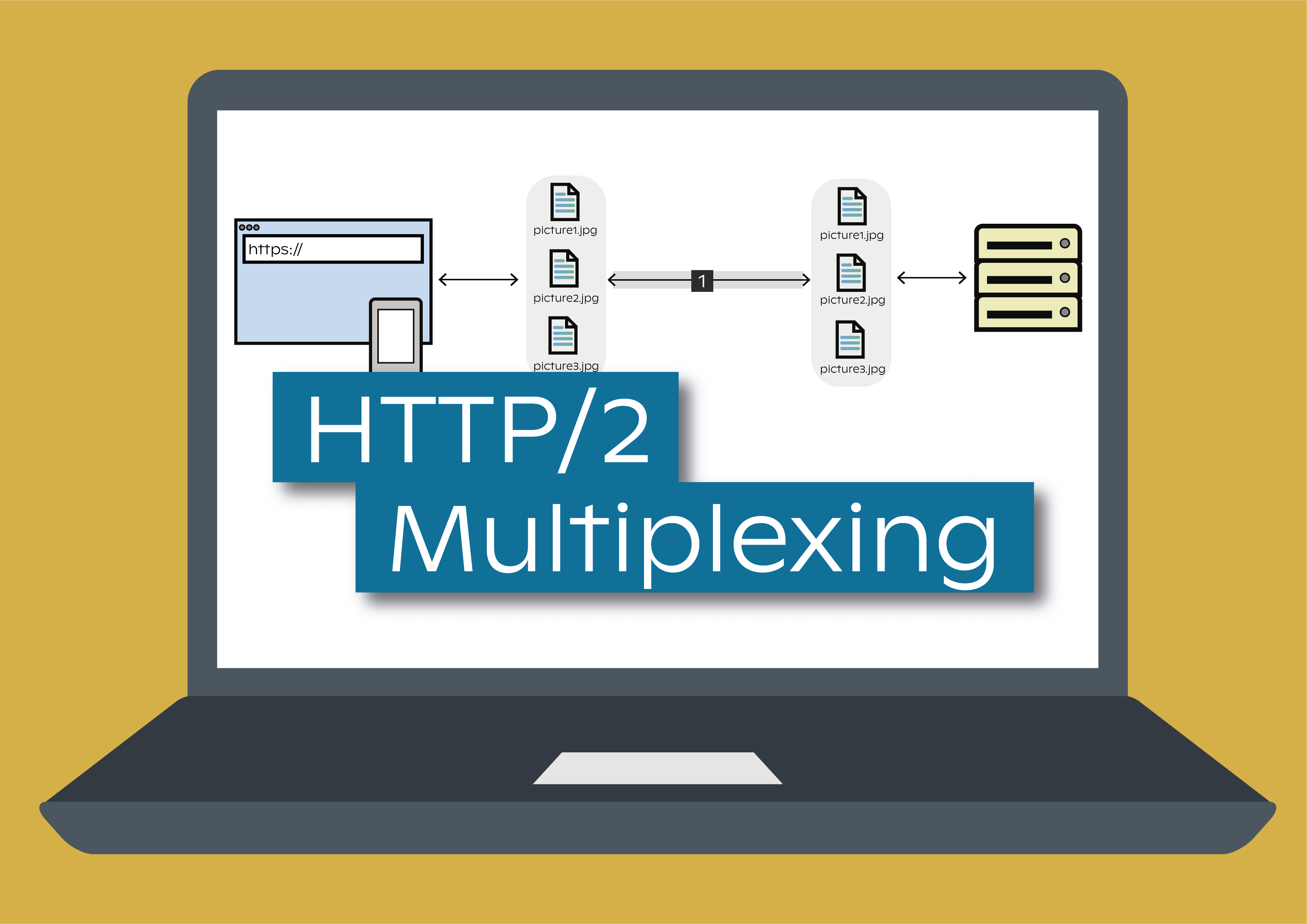

In this post I explore one of its most cool and promising features: HTTP/2 multiplexing. I’ll guide you through understanding HTTP/2 multiplexing behavior (where multiple requests share the same connection), to then compare it with the option of performing multiple requests over multiple connections.

A brief flashback

HTTP was created at the beginning of the 90s, and its first version was HTTP/0.9 (how typical of engineers, to release a beta version..!). Since then, it had 3 more major iterations or versions: HTTP/1.0, HTTP/1.1, and the latest one, HTTP/2. Currently, there is a proposal for a fifth iteration, HTTP/3, which is now on standardization stage. In a nutshell, consists of bringing HTTP over QUIC for the masses.

Exploring HTTP/2 Multiplexing

HTTP/2 is a protocol that was highly inspired by Google’s SPDY protocol. SPDY’s goal was to reduce the web page load time by compressing, multiplexing and prioritizing HTTP requests. Multiplexing HTTP requests allows the usage of a single connection per client, meaning that a single connection between the client and the webserver can be used to serve all requests asynchronously, enabling the webserver to use less resources, thus support more users at the same time.

![]()

I see… Does it means that, when possible, I should use HTTP/2, and when performing multiple parallel requests, I should use HTTP/2’s multiplexing?

Yes and no… It’s complicated. When performing multiple parallel requests, there are two approaches: multiplex multiple requests over a single connection, or performing multiple requests over multiple connections.

HTTP multiplexing saves resources by sharing the connection, but notice that this connection is a TCP connection. This means that if a single TCP is capable of fully utilize the channel capacity (this is, the TCP connection can make use of the full bandwidth available), then yes, HTTP multiplexing will be the best bet.

However, if a single TCP connection cannot fully use of the channel, then opening multiple connections will achieve better performance. - This can occur due to the way TCP’s congestion avoidance mechanisms manage and understand packet losses. - In this scenario, multiple connections will achieve a high transfer throughput then a single connection.

Ok, all fine. But can’t I achieve a similar behavior to multiplexing with HTTP/1.1?

HTTP/1.1 client libraries can use a mechanism called connection pool, where connections can be shared. However, this is not the same as multiplexing. If multiple HTTP requests are performed in a very short span of time, HTTP/1.1 has no way to share those connections. Therefore, it will create new connections to the content server for each HTTP request.

Makes sense. By the way, how do I make sure that I am using HTTP/2 properly?

You have at least 2 ways to verify if HTTP/2 (or any HTTP version, in fact) is working as intended: either looking to your client debug tool (app or web browser) or looking at the logs of the web server. To help exemplifying this, I created an Android app to perform simple HTTP requests and an HTTP web server, based on Nginx, which will serve those HTTP requests. I decided to use an app over a web browser due to the app’s easiness to create the intended use cases.

The Android app, performs four types of HTTP requests (more specifically, each type consists of 5 parallel HTTP requests), of a 2.8MB image:

- A - HTTP/1.1 requests forcing a single connection

- B - HTTP/1.1 requests allowing multiple connections

- C - HTTP/2 requests using multiple connections

- D - HTTP/2 requests multiplexed in a single connection

Looking to the app side

The app uses the powerful OkHTTP library to perform the HTTP requests. This library works with all HTTP versions (currently up to HTTP/2) and, depending on the way you set it up, OkHTTP can make use of connection pooling on HTTP/1.1 or multiplexing on HTTP/2.

Using the Android Studio profiler tool, we can see how the HTTP requests are being performed. Here is an example of the four requests.

A - HTTP/1.1 requests forcing a single connection

Given that HTTP/1.1 is not capable of performing multiple HTTP requests on the same connection and that we are forcing a single connection, the 5 parallel HTTP requests are performed sequentially (indicated on the waterfall). A single TCP connection is shared among the 5 HTTP requests (indicated on the dashed yellow line on the top time graph).

B - HTTP/1.1 requests allowing multiple connections

The HTTP requests are truly performed in parallel (see the waterfall). As expected, 5 TCP connections are open, given that HTTP/1.1 is not capable of performing multiple HTTP requests on the same connection (indicated on the dashed yellow line on the top time graph).

C - HTTP/2 requests using multiple connections

The HTTP requests behave exactly like in set B. This is expected, since we are not enabling multiplexing of multiple requests.

D - HTTP/2 requests multiplexed in a single connection

HTTP requests are performed in parallel, (indicated on waterfall) and the client is only using a single TCP connection (indicated on the dashed yellow line on the top time graph).

General considerations

Our analysis to the client data indicates that all four sets of HTTP requests achieve very similar transfer speeds. This occurs because a single TCP connection is capable of making full use of the available channel capacity.

However, notice that the app UX is different for set A when compared to the other three sets. In the set A, the app after 1.7 seconds is capable of start showing some content to the user, which is opposite to the other sets, where the app needs to wait for some 5~7 seconds before showing any content to the user. This can be a deal breaker for apps like video streaming apps, were different requests have different priorities.

Looking to the webserver side

I configured a Nginx server to serve the HTTP requests to the client app and then looked to its logs, in order to assess the number of connections used and the reuse of connections. To achieve this, I will make use of the $connection log to fetch the connection serial number (each connection will be shown with a unique connection id) and the $connection_requests log to fetch the number of requests performed through that connection (nginx log modules).

A - HTTP/1.1 requests forcing a single connection

A single connection is open to the web server and all HTTP requests are performed in that connection.

B - HTTP/1.1 requests allowing multiple connections

As expected, each HTTP request creates a new connection to the webserver.

C - HTTP/2 requests using multiple connections

It behaves just like set B, where each HTTP request creates a new connection to the webserver.

D - HTTP/2 requests multiplexed in a single connection

A single connection is made to the web server and all HTTP requests are sharing that connection.

Final thoughts

HTTP/2 multiplexing is a nice tool to have at our disposal. However, it is not the perfect solution to all problems. We need to fully understand the benefits and drawbacks of each approach, and it is really important to know how to measure and evaluate how each approach is working.

If a single connection is capable of using the full channel capacity, then HTTP/2 multiplexing is the way to go. If a single connection is not capable of using the full channel capacity, then performing HTTP requests over multiple connections may be a better option.

However, if your major concern is server resource usage, then you should prioritize approaches such as HTTP/2 multiplexing, given that they minimize the number of connections between clients and the webserver. Remember: with fewer resources used, more clients can be served at the same time.

Also, consider the effect of your request’s choices for the UX. Parallelize multiple requests may not be the best approach, and you should not use it every single time.

The code used for the Android app is available in this Github project and a project with a docker image containing the web server used is available in this Github project. Feel free to adapt them to your specific needs.

Happy coding!